Scrum Process Template Vision

About Scrum A Management Framework Scrum is a management framework for incremental product development using one or more cross-functional, self-organizing teams of about seven people each. It provides a structure of roles, meetings, rules, and artifacts. Teams are responsible for creating and adapting their processes within this framework. Scrum uses fixed-length iterations, called Sprints, which are typically 1-2 weeks long (never more than 30 days). Scrum teams attempt to build a potentially shippable (properly tested) product increment every iteration.

An Alternative to Waterfall Scrum’s incremental, iterative approach trades the traditional phases of “waterfall” development for the ability to develop a subset of high-value features first, incorporating feedback sooner. Figure 2: Scrum blends all development activities into each iteration, adapting to discovered realities at fixed intervals. The greatest potential benefit of Scrum is for complex work involving knowledge creation and collaboration, such as new product development. Scrum is usually associated with object-oriented software development.

Its use has also spread to the development of products such as semiconductors, mortgages, and wheelchairs. Doing Scrum, or Pretending to Do Scrum? Scrum’s relentless reality checks expose dysfunctional constraints in individuals, teams, and organizations. Many people claiming to do Scrum modify the parts that require breaking through organizational impediments and end up robbing themselves of most of the benefits. Figure 3: Scrum flow All Scrum Meetings are facilitated by the ScrumMaster, who has no decision-making authority at these meetings.

Sprint Planning Meeting At the beginning of each Sprint, the Product Owner and team hold a Sprint Planning Meeting to negotiate which Product Backlog Items they will attempt to convert to working product during the Sprint. The Product Owner is responsible for declaring which items are the most important to the business. The team is responsible for selecting the amount of work they feel they can implement without accruing technical debt. The team “pulls” work from the Product Backlog to the Sprint Backlog. When teams are given complex work that has inherent uncertainty, they must work together to intuitively gauge their capacity to commit to items, while learning from previous Sprints. Planning their hourly capacity and comparing their estimates to actuals makes the team pretend to be precise and reduces ownership of their commitments. Unless the work is truly predictable, they should discard such practices within the first few Sprints or avoid them altogether.

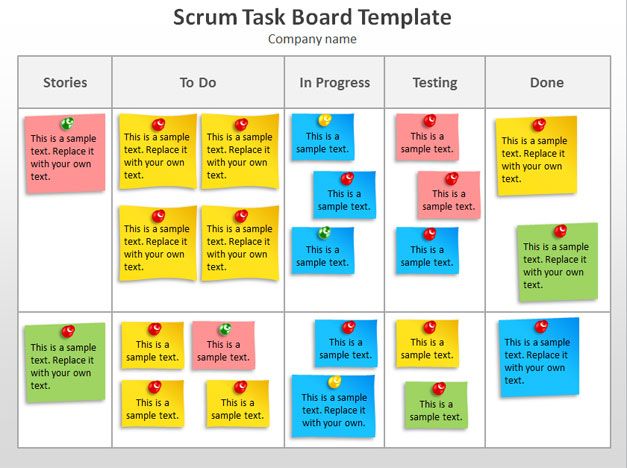

Scrum Board Template

Until a team has learned how to complete a potentially-shippable product increment each Sprint, it should reduce the amount of functionality it commits to. Failure to change old habits leads to technical debt and eventual design death, as shown in Figure 15. If the top of the Product Backlog has not been refined, a major portion of the planning meeting should be spent doing this, as described in the Backlog Refinement Meeting section. Toward the end of the Sprint Planning Meeting, the team breaks the selected items into an initial list of Sprint Tasks, and makes a final commitment to do the work. The maximum allotted time (a.k.a. Timebox) for planning a 30-day Sprint is eight hours, reduced proportionally for a shorter Sprint.

Figure 4: Sprint Planning Meeting outcome is committed Product Backlog Items (PBIs) and subordinate Sprint Tasks. Daily Scrum and Sprint Execution Every day at the same time and place, the Scrum Development Team members spend a total of 15 minutes reporting to each other. Each team member summarizes what he did the previous day, what he will do today, and what impediments he faces. Standing up at the Daily Scrum will help keep it short. Topics that require additional attention may be discussed by whomever is interested after every team member has reported. The team may find it useful to maintain a current Sprint Task List, a Sprint Burndown Chart, and an Impediments List. During Sprint execution it is common to discover additional tasks necessary to achieve the Sprint goals.

Impediments caused by issues beyond the team’s control are considered organizational impediments. It is almost always useful for the Product Owner to attend the Daily Scrum. But when any attendee also happens to be the team’s boss, the invisible gun effect hampers self-organization and emergent leadership. People lacking real experience of team self-organization won’t see this problem, just as fish are unaware of water. Conversely, a team that needs additional expertise in product requirements will benefit from increased Product Owner involvement, including Daily Scrum attendance. The Daily Scrum is intended to disrupt old habits of working separately. Members should remain vigilant for signs of the old approach.

For example, looking only at the ScrumMaster when speaking is one symptom that the team hasn’t learned to operate as a self-organizing entity. Sprint Review Meeting After Sprint execution, the team holds a Sprint Review Meeting to demonstrate a working product increment to the Product Owner and everyone else who is interested. The meeting should feature a live demonstration, not a report. After the demonstration, the Product Owner reviews the commitments made at the Sprint Planning Meeting and declares which items he now considers done. For example, a software item that is merely “code complete” is considered not done, because untested software isn’t shippable. Incomplete items are returned to the Product Backlog and ranked according to the Product Owner’s revised priorities as candidates for future Sprints.

The ScrumMaster helps the Product Owner and stakeholders convert their feedback to new Product Backlog Items for prioritization by the Product Owner. Often, new scope discovery outpaces the team’s rate of development. If the Product Owner feels that the newly discovered scope is more important than the original expectations, new scope displaces old scope in the Product Backlog. The Sprint Review Meeting is the appropriate meeting for external stakeholders (even end users) to attend. It is the opportunity to inspect and adapt the product as it emerges, and iteratively refine everyone’s understanding of the requirements. New products, particularly software products, are hard to visualize in a vacuum.

Many customers need to be able to react to a piece of functioning software to discover what they will actually want. Iterative development, a value-driven approach, allows the creation of products that couldn’t have been specified up front in a plan-driven approach. Given a 30-day Sprint (much longer than anyone recommends nowadays), the maximum time for a Sprint Review Meeting is four hours. Sprint Retrospective Meeting Each Sprint ends with a retrospective.

At this meeting, the team reflects on its own process. They inspect their behavior and take action to adapt it for future Sprints. Dedicated ScrumMasters will find alternatives to the stale, fearful meetings everyone has come to expect. An in-depth retrospective requires an environment of psychological safety not found in most organizations. Without safety, the retrospective discussion will either avoid the uncomfortable issues or deteriorate into blaming and hostility. A common impediment to full transparency on the team is the presence of people who conduct performance appraisals. Another impediment to an insightful retrospective is the human tendency to jump to conclusions and propose actions too quickly.

Agile Retrospectives, the most popular book on this topic, describes a series of steps to slow this process down: Set the stage, gather data, generate insights, decide what to do, close the retrospective. (1) Agile Retrospectives, Pragmatic Bookshelf, Derby/Larson (2006) Another guide recommended for ScrumMasters, The Art of Focused Conversations, breaks the process into similar steps: Objective, reflective, interpretive, and decisional (ORID). (2) The Art of Focused Conversations, New Society Publishers (2000) A third impediment to psychological safety is geographic distribution.

Scrum Process Flow

Geographically dispersed teams usually do not collaborate as well as those in team rooms. Retrospectives often expose organizational impediments. Once a team has resolved the impediments within its immediate influence, the ScrumMaster should work to expand that influence, chipping away at the organizational impediments. ScrumMasters should use a variety of techniques to facilitate retrospectives, including silent writing, timelines, and satisfaction histograms. In all cases, the goals are to gain a common understanding of multiple perspectives and to develop actions that will take the team to the next level. Backlog Refinement Meeting Most Product Backlog Items (PBIs) initially need refinement because they are too large and poorly understood.

Teams have found it useful to take a little time out of Sprint Execution — every Sprint — to help prepare the Product Backlog for the next Sprint Planning Meeting. In the Backlog Refinement Meeting, the team considers the effort they would expend to complete items in the Product Backlog and provides other technical information to help the Product Owner prioritize them. (3) The team should collaborate to produce a jointly-owned estimate for an item. See Large vague items are split and clarified, considering both business and technical concerns.

Sometimes a subset of the team, in conjunction with the Product Owner and other stakeholders, will compose and split Product Backlog Items before involving the entire team in estimation. A skilled ScrumMaster can help the team identify thin vertical slices of work that still have business value, while promoting a rigorous definition of “done” that includes proper testing and refactoring. It is common to write Product Backlog Items in User Story form.

( 4) User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development, Addison Wesley, Cohn (2004) In this approach, oversized PBIs are called epics. Traditional development breaks features into horizontal tasks (resembling waterfall phases) that cannot be prioritized independently and lack business value from the customer’s perspective. This habit is hard to break. Agility requires learning to split large epics into user stories representing very small product features.

For example, in a medical records application the epic “display the entire contents of a patient’s allergy records to a doctor” yielded the story “display whether or not any allergy records exist.” While the engineers anticipated significant technical challenges in parsing the internal aspects of the allergy records, the presence or absence of any allergy was the most important thing the doctors needed to know. Collaboration between business people and technical people to split this epic yielded a story representing 80% of the business value for 20% of the effort of the original epic.

Since most customers don’t use most features of most products, it’s wise to split epics to deliver the most valuable stories first. While delivering lower-value features later is likely to involve some rework, rework is better than no work. The Backlog Refinement Meeting lacks an official name and has also been called “Backlog Grooming,” “Backlog Maintenance,” or “Story Time.”. Figure 7: A PBI represents a customer-centric feature, usually requiring several tasks to achieve definition of done.

Figure 10: Sprint tasks required to complete one backlog item require a mix of activities no longer done in separate phases (e.g., requirements elicitation, analysis, design, implementation, deployment, testing). Sprint Burndown Chart. Indicates total remaining team task hours within one Sprint. Re-estimated daily, thus may go up before going down. Intended to facilitate team self-organization.

Fancy variations, such as itemizing by point person or adding trend lines, tend to reduce effectiveness at encouraging collaboration. Seemed like a good idea in the early days of Scrum, but in practice has often been misused as a management report, inviting intervention. The ScrumMaster should discontinue use of this chart if it becomes an impediment to team self-organization.

Figure 12: A Release Burndown Chart variation popularized by Mike Cohn. ( Agile Estimation and Planning, Cohn, Addison Wesley (2006)) The red line tracks PBIs completed over time (velocity), while the blue line tracks new PBIs added (new scope discovery). The intersection projects release completion date from empirical trends. Scaling Bad News: It’s Hard. Scrum addresses uncertain requirements and technology risks by grouping people from multiple disciplines into one team (ideally in one team room) to maximize communication bandwidth, visibility, and trust. When requirements are uncertain and technology risks are high, adding too many people to the situation makes things worse.

Grouping people by specialty also makes things worse. Grouping people by architectural components (a.k.a. Component teams) makes things worse. Figure 14: Feature teams learn to span architectural components. More Bad News: It’s Still Hard.

Large organizations are particularly challenged when it comes to Agility. Most have not gotten past pretending to do Scrum. (6) “Seven Obstacles to Enterprise Agility,” Gantthead, James (2010) ScrumMasters in large organizations should promote transformation and remove organizational impediments. (7) Scaling Lean & Agile Development, Larman/Vodde, Addison Wesley (2008) Large Scale Scrum (LeSS) To learn more about large scale Agile development see.

Related Practices Lean Scrum is a general management framework coinciding with the Agile movement in software development, which is partly inspired by Lean manufacturing approaches such as the Toyota Production System. (8) Toyota Production System: eXtreme Programming (XP) While Scrum does not prescribe specific engineering practices, ScrumMasters are responsible for promoting increased rigor in the definition of done. Items that are called “done” should stay done. Automated regression testing prevents vampire stories that leap out of the grave. Design, architecture, and infrastructure must emerge over time, subject to continuous reconsideration and refinement, instead of being “finalized” at the beginning, when we know nothing. The ScrumMaster can inspire the team to learn engineering practices associated with XP: Continuous Integration (continuous automated testing), Test-Driven Development (TDD), constant merciless refactoring, pair programming, frequent check-ins, etc.

Informed application of these practices prevents technical debt. Figure 15: The straight green line represents the general goal of Agile methods: early and sustainable delivery of valuable features. Doing Scrum properly entails learning to satisfy a rigorous definition of “done” to prevent technical debt. (Graph inspired by discussions with Ronald E. Jeffries) Team Self-Organization Engaged Teams Outperform Manipulated Teams During Sprint execution, team members develop an intrinsic interest in shared goals and learn to manage each other to achieve them. The natural human tendency to be accountable to a peer group contradicts years of habit for workers.

Allowing a team to become self-propelled, rather than manipulated through extrinsic punishments and rewards, contradicts years of habit for managers. (10) Intrinsic motivation is linked to mastery, autonomy, and purpose. “Rewards” harm this The ScrumMaster’s observation and persuasion skills increase the probability of success, despite the initial discomfort. Challenges and Opportunities Self-organizing teams can radically outperform larger, traditionally managed teams. Family-sized groups naturally self-organize when the right conditions are met:.

members are committed to clear, short-term goals. members can gauge the group’s progress. members can observe each other’s contribution. members feel safe to give each other unvarnished feedback Psychologist Bruce Tuckman describes stages of group development as “forming, storming, norming, performing.” (11) “Developmental Sequence in Small Groups.” Psychological Bulletin, 63 (6): 384-99 Tuckman, referenced repeatedly by Schwaber. Optimal self-organization takes time. The team may perform worse during early iterations than it would have performed as a traditionally managed working group.

(12) The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization, Katzenbach, Harper Business (1994) Heterogeneous teams outperform homogeneous teams at complex work. They also experience more conflict. (13) Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration, Sawyer, Basic Books (2007). (This book is #2 on Michael James’s list of recommended reading for ScrumMasters.) Disagreements are normal and healthy on an engaged team; team performance will be determined by how well the team handles these conflicts. Bad apple theory suggests that a single negative individual (“withholding effort from the group, expressing negative affect, or violating important interpersonal norms” (14) “How, when, and why bad apples spoil the barrel: Negative group members and dysfunctional groups.” Research in Organizational Behavior, Volume 27, 181–230, Felps/Mitchell/Byington, (2006) ) can disproportionately reduce the performance of an entire group. Such individuals are rare, but their impact is magnified by a team’s reluctance to remove them.

This can be partly mitigated by giving teams greater influence over who joins them. Other individuals who underperform in a boss/worker situation (due to being under-challenged or micromanaged) will shine on a Scrum team.

Self-organization is hampered by conditions such as geographic distribution, boss/worker dynamics, part-time team members, and interruptions unrelated to Sprint goals. Most teams will benefit from a full-time ScrumMaster who works hard to mitigate these kinds of impediments. (15) An example detailed list of full-time ScrumMaster responsibilities: When is Scrum Appropriate? Figure 16: Scrum, an empirical framework, is appropriate for work with uncertain requirements and/or uncertain technology issues. Scrum is intended for the kinds of work people have found unmanageable using defined processes — uncertain requirements combined with unpredictable technology implementation risks. When deciding whether to apply Scrum, as opposed to plan-driven approaches such as those described by the PMBOK ® Guide, consider whether the underlying mechanisms are well-understood or whether the work depends on knowledge creation and collaboration. For example, Scrum was not originally intended for repeatable types of production and services.

Also consider whether there is sufficient commitment to grow a self-organizing team. ↓. Archie Please see me a PDF copy of this!

Great read thanks! I have a question – Are time estimates done in actual times like hours etc? I have a colleague who says it goes by complexity only points. I don’t understand how you would get a time from this? The way I understand time estimates, is review each story. Get it a rough time estimate of completion along with a complexity number i.e for very complex features 5, relatively straight forward features 1.

Then X them together? Any techniques here would be great! Thanks in advance.

Archie – Project Manager, coming away from PRINCE 2 Agile:D. ↓. Kristy First off, MJ, thank you so much for this guide. I was prompted by an interviewer to ‘go study scrum’ and with this guide, you have enabled me to learn so much information, at my own rate of time, and for free. On top of the guide and your digital reference card, you’re mailing glossy colored copies to people for free! This is just amazingly generous of you and I wanted to point that out.

And thank you! Adding in response to that, though, I’m noticing a large number of responders who did not follow your one and only instruction, posted at the top of this commentary, and even in bold. It’s doubtful a repeat of this by myself at the bottom will help but here it is anyway. MJ Post author April 4, 2014 at 11:01 pm Send me a private email (mj4scrum at Google’s mailing service dot com) with mailing address and desired quantity and we’ll mail them out to you.

Please do not post your street addresses here, as everyone in the world will be able to read them. I do wonder if, as a moderator type role, if you (or another with moderator type abilities) might have the ability and the willingness to ‘hide’ the more sensitive portions of information so many people have already publicly posted here? ↓. Laura Soranno Hello Michael, This reference card and your training series are excellent resources. As a coach, I have a stack of reference cards and a sign “take one” hanging outside my work space as an information radiator.

This has led to some great introductions and input. Thank you so much for your excellent work! For the Scaling section, I wonder if including SAFe concepts may make sense. We are seeing some very good scaling using these methods. Yes, it is still difficult, but becoming a bit more doable and measurable with SAFe. Best regards, Laura.

↓. MJ Post author Laura, yeah, the scaling section of the card is very thin right now. SAFe seems to be better than what most organizations are currently doing, but to me it looks more like an 80% traditional, 20% agile hybrid approach.

A client of mine wrote “Well, we sorta tried to do the Leffingwell stuff again recently, but I am for sure ready to throw the book in the river.” My concern is that SAFe’s contradictions with Agile principles will not create as adaptable an organization as possible, and this will be blamed on Agile even though (as Ron Jeffries wrote) “SAFe is not Agile at its core.” A more principled set of ideas is now being called. My question is: will this more radical approach will be palatable to many organizations that fundamentally don’t want to change? ↓. Donald Britz I am leading my company through a ‘baptism by fire’ transition from Waterfall to Agile. The Scrum Reference Card document is really well put together and will serve as a neat ‘ready reference’ document for those across the organisation who are having conceptual difficulties with the transition I will be most grateful if you could send to me 10 glossy copies of the Scrum Reference Card. My address is: Donald Britz, 3 Quarry Farm, South Tawton, near Okehampton, Devon, EX20 2RH, England.

In hopeful anticipation Thank you.